what product did western merchants choose to get the chinese to buy in large quanities

| Introduction The Opium Wars of 1839 to 1842 and 1856 to 1860 marked a new stage in Red china's relations with the West. Mainland china's military defeats in these wars forced its rulers to sign treaties opening many ports to foreign trade. The restrictions imposed nether the Canton system were abolished. Opium, despite regal prohibitions, now became a regular item of trade. Equally opium flooded into Mainland china, its cost dropped, local consumption increased quickly, and the drug penetrated all levels of order. In the new treaty ports, foreign traders collaborated with a greater diversity of Chinese merchants than under the Canton arrangement, and they ventured deeply into the Chinese interior. Missionaries brought Christian teachings to villagers, protected by the diplomatic rights obtained under the treaties. Popular hostility to the new foreigners began to rise. Not surprisingly, Chinese historians have regarded the two Opium Wars as unjust impositions of foreign power on the weakened Qing empire. In the 20th century, the Democracy of China made strenuous efforts to abolish what it called "diff treaties." It succeeded in removing near of them in Globe War II, but this phase of foreign imperialism only ended completely with the reversion of Hong Kong to China in 1997. Conventional textbooks even date the beginning of modernistic Chinese history from the end of the beginning Opium War in 1842. Although the wars, opium merchandise, and treaties did reflect superior Western armed services force, focusing but on Western impositions on Red china gives us likewise narrow a motion-picture show of this period. This was not only a time of Western and Chinese conflict over trade, simply a time of great global transformation in which Prc played one important function. The traders in opium included Great britain, the U.Due south., Turkey, Bharat, and Southeast Asia as well as domestic Chinese merchants. The origins of opium consumption in China are very erstwhile, and its commencement real nail as an item of consumption began after tobacco was introduced from the New World in the 16th century and Chinese smokers took a fancy to mixing it with the drug. The Qing courtroom was not in principle hostile to useful merchandise. In 1689 and 1727, the courtroom had negotiated treaties with Russia to commutation furs from Siberia for tea, and allowed the Russians to live in a foreigners' guest business firm in Beijing. Qing merchants and officials likewise traded extensively with Central Eurasian merchants from Bukhara and the Kazakh nomads for vital supplies of wool, horses, and meat. The court knew well the value of the southern littoral merchandise equally well, since revenues from the County trade went straight into the Imperial Household section. The Opium Wars are rightly named: it was not trade per se merely rather unrestricted drug merchandise past the Western powers, particularly Britain, that precipitated them. As the wars unfolded, nevertheless, information technology became clear that far more than opium was ultimately involved. The very nature of Mainland china's hitherto aloof relationship with the world was greatly challenged, and long decades of internal upheaval lay ahead. Tensions Nether the Canton Trade Organisation Under the organization established past the Qing dynasty to regulate trade in the 18th century, Western traders were restricted to conducting trade through the southern port of Canton (Guangzhou). They could simply reside in the metropolis in a limited space, including their warehouses; they could not bring their families; and they could non stay in that location more a few months of the yr. Qing officials closely supervised trading relations, assuasive only licensed merchants from Western countries to trade through a monopoly social club of Chinese merchants called the Cohong. Western merchants could not contact Qing officials directly, and at that place were no formal diplomatic relations betwixt Cathay and Western countries. The Qing emperor regarded merchandise equally a grade of tribute, or gifts given to him personally by envoys who expressed gratitude for his benevolent rule. |

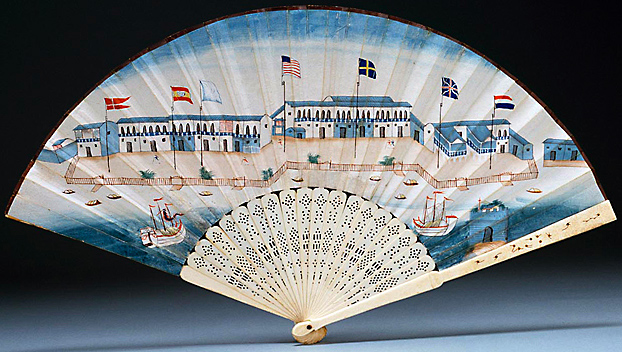

| Canton, where the business organisation of trade was primarily conducted during this period, is depicted on this fan created for the foreign market. 7 national flags wing from the Western headquarters that line the shore. Chinese Fan with Foreign Factories at Canton, 1790�1800 Peabody Essex Museum [cwOF_1790c_E80202_fan] |

| Western traders, for their role, mainly conducted trade through licensed monopoly companies, like Britain'south Due east Republic of india Company and the Dutch VOC. Despite these restrictions, both sides learned how to make profits by cooperating with each other. The Chinese hong merchants, the central intermediaries betwixt the strange traders and the officials, developed close relations with their Western counterparts, instructing them on how to bear their business without antagonizing the Chinese hierarchy. As the volume of merchandise grew, still, the British demanded greater access to China'southward markets. Tea exports from Communist china grew from 92,000 pounds in 1700 to ii.seven meg pounds in 1751. Past 1800 the East Bharat Visitor was buying 23 1000000 pounds of tea per year at a cost of three.6 meg pounds of silver. Concerned that the Mainland china merchandise was draining silver out of England, the British searched for a analogue commodity to merchandise for tea and porcelain. They found information technology in opium, which they planted in big quantities after they had taken Bengal, in India, in 1757. British merchants blamed the restrictions of the Canton merchandise for the failure to export plenty goods to Communist china to balance their imports of tea and porcelain. Thus, Lord George Macartney's mission to the courtroom in Beijing in 1793 aimed to promote British trade by creating direct ties between the British government and the emperor. Macartney, all the same, portrayed his diplomatic mission as a tribute mission to celebrate the emperor's altogether. He had only one man with him who could speak Chinese. When he tried to enhance the merchandise question, after post-obit the tribute rituals, Macartney's demands were rejected. His gifts of astronomical instruments, intended to impress the Qing emperor with British technological skills, in fact did not wait very impressive: the emperor had already received similar items from Jesuits in earlier decades. Macartney's failure, and the failure of a later mission (the Amherst embassy) in 1816, helped to convince the British that only force would induce the Qing authorities to open China's ports. Opium Clippers & the Expanding Drug Trade |

| Opium routes between British-controlled India and China [map_OpRoutes_BrEmpire21_234-5] |

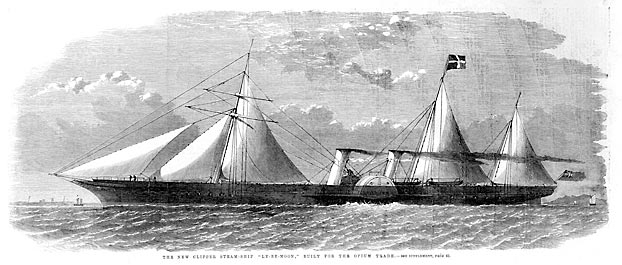

| New fast sailing vessels called clipper ships, built with narrow decks, large sail areas, and multiple masts, first appeared in the Pacific in the 1830s and greatly stimulated the tea trade. They carried less cargo than the bulky East Indiamen, simply could bring fresh teas to Western markets much faster. Clipper ships besides proved very user-friendly for smuggling opium, and were openly and popularly identified equally "opium clippers." Ships like the Red Rover could bring opium chop-chop from Calcutta to Canton, doubling their owners' profits by making two voyages a yr. At Canton, Qing prohibitions had forced the merchants to withdraw from Macao (Macau) and Whampoa and retreat to Lintin island, at the entrance of the Pearl River, across the jurisdiction of local officials. There the merchants received opium shipments from Republic of india and handed the chests over to modest Chinese junks and rowboats chosen "fast venereal" and "scrambling dragons," to be distributed at small-scale harbors along the declension. The latter local smuggling boats were sometimes propelled by equally many as xx or more than oars on each side. |

| The Pearl River Delta [map_MouthCantonRiver_p79747] |

The major India source of British opium bound for China was Patna in Bengal, where the drug was processed and packed into chests belongings nigh 140 pounds. The almanac flow to China was around iv,000 chests by 1790, and a little more than double this by the early 1820s. Imports began to increase quickly in the 1830s, nonetheless, equally "free trade" agitation gained force in Britain and the East India Company's monopoly over the Communist china trade approached its termination date (in 1834). The Company became more dependent than ever on opium revenue, while individual merchants hastened to increase their stake in the lucrative trade. On the eve of the offset Opium War, the British were aircraft some 40,000 chests to China annually. By this appointment, information technology was estimated that there were probably around ten million opium smokers in Prc, two million of them addicts. (American merchants shipped around ten,000 chests betwixt 1800 to 1839.)

|

| "The Opium Ships at Lintin in Communist china, 1824" Print based on a painting by "W. J. Huggins, Marine Painter to His late Majesty William the fourth" National Maritime Museum [1824_PZ0240_Lintin_nmm] |

| In 1831, it was estimated that between 100 and 200 "fast crab" smuggling boats were operating in the waters effectually Lintin Island, the rendezvous bespeak for opium imports. Ranging from xxx to seventy feet in length, with crews of upwards of 50 or 60 men, these swift rowboats could put on sail for additional speed. They were critical in navigating China'southward often shallow rivers and delivering opium to the interior."Fast Boat or Smuggler," from Captain E. Belcher, Narrative of a Voyage Round the World (1843), p. 238 [1843_belcher_238_FastBoat] |

| "The 'Streatham' and the opium clipper 'Red Rover'" The Streatham, an East India Visitor send, is shown at ballast in the Hooghly River, Calcutta. Near the bank, the Red Rover, the first of the "opium clippers," sits with her sails lowered. Built for speed, the Red Rover doubled the profits of her owners by completing two Calcutta-to-China smuggling voyages a yr. [BHC3580_opiumcl_nmm] |

| "The new clipper steam-ship "LY-EE-MOON," built for the opium merchandise," Illustrated London News, ca. 1859A quarter century later on revolutionizing the drug merchandise, the celebrated "opium clippers" had begun to undergo a further revolution with the improver of coal-fueled, steam-driven paddle wheels. This illustration appeared in the Illustrated London News in 1859, two decades afterwards the outset Opium War began. [1800s_LyEeMoonILN_Britannca] |

| Mandarins, Merchants & Missionaries The opium trade was so vast and profitable that all kinds of people, Chinese and foreigners, wanted to participate in it. Wealthy literati and merchants were joined past people of lower classes who could at present beget cheaper versions of the drug. Hong merchants cooperated with foreign traders to smuggle opium when they could get away with it, bribing local officials to look the other fashion. Smugglers, peddlers, clandestine societies, and even banks in certain areas all became complicit in the drug trade. |

| Illustrated London News, Nov 12, 1842 [iln_1842_174_mandarins_012b] |

| Three paintings of the Chinese hong merchants (details) Left: Howqua, by George Chinnery, 1830 Middle: Mowqua, by Lam Qua, 1840s Right: Tenqua, by Lam Qua, ca. 1840s Peabody Essex Museum [cwPT_1830_howqua_chinnery] [cwPT_1840s_ct79_Mouqua] [cwPT_1840s_ct78_Tenqua] |

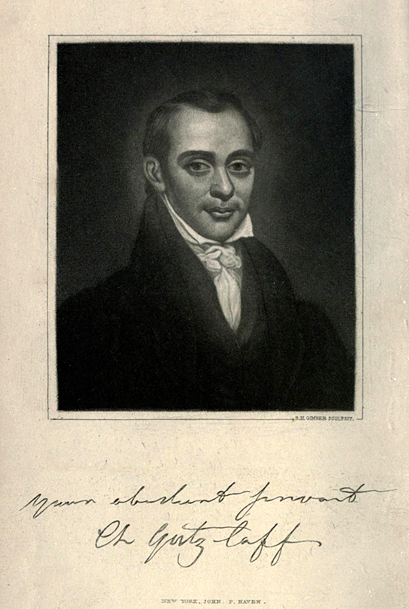

| Opium, every bit an illegal commodity, brought in no customs acquirement, so local officials exacted fees from merchants. Even missionaries who deplored the opium trade on moral grounds commonly found themselves drawn into information technology, or dependent on information technology, in one form or some other. They relied on the opium clippers for transportation and communication, for example, and used merchants dealing in opium equally their bankers and money changers. Karl Gützlaff (1803–1851), a Protestant missionary from Pomerania who was an exceptionally gifted linguist, gained a modicum of both fame and notoriety by becoming closely associated with the opium merchandise and then serving the British in the Opium War—not just as an interpreter, just as well as an ambassador in areas occupied by the foreign forces. |

| Portrait of Gützlaff (inscribed) on the frontispiece of his 1834 volume, A Sketch of Chinese History: Ancient and Modern. [1834_Gutzlaff_SHG_fron#E38B] |

| |  Peabody Essex Museum Peabody Essex Museum[1832_M976541_Gutzlaff_pem] Wikimedia Commons Karl_Gutzlaff.jpg [1832c_KarlGutzlaff_wp] |

| The Daoguang Emperor & Commissioner Lin By the 1830s, up to 20 percentage of key government officials, 30 percent of local officials, and thirty percent of low-level officials regularly consumed opium. The Daoguang emperor (r. 1821–50) himself was an addict, as were nigh of his courtroom. As opium infected the Qing war machine forces, still, the courtroom grew alarmed at its insidious effects on national defense. Opium imports also appeared to exist the cause of massive outflows of silver, which destabilized the currency. While the court repeatedly issued edicts demanding penalization of opium dealers, local officials accepted heavy bribes to ignore them. In 1838, one opium dealer was strangled at Macao, and eight chests of opium were seized in Canton. Still the emperor had not yet resolved to take truly decisive measures. |

| |

| |  |

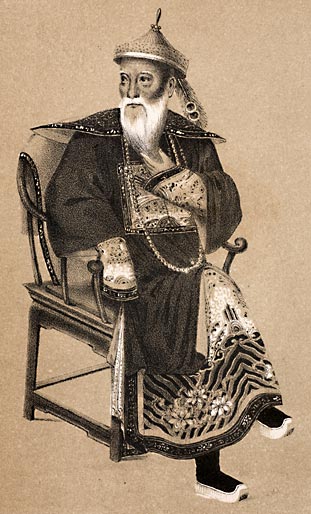

| "Mien-Ning, |

| As opium flooded the state despite imperial prohibitions, the court debated its response. On ane side, officials concerned virtually the economical costs of the silvery drain and the social costs of addiction argued for stricter prohibitions, aimed not only at Chinese consumers and dealers but also at the foreign importers. On the other side, a mercantile interest including southern coastal officials allied with local traders promoted legalization and taxation of the drug. Fence raged within court circles in the early 1800s as factions lined upward patrons and pushed their favorite policies. Ultimately, the Daoguang emperor decided to support hardliners who called for complete prohibition, sending the influential official Lin Zexu to Canton in 1839. Lin was a morally upright, energetic official, who detested the corruption and decadence created by the opium trade. He had served in many important provincial posts effectually the empire and gained a reputation for impartiality and dedication to the welfare of the people he governed. In July 1838 he sent a memorial to the emperor supporting desperate measures to suppress opium employ. He outlined a systematic policy to destroy the sources and equipment supporting drug utilise, and began putting this policy into effect in the provinces of Hubei and Hunan. Afterwards 19 audiences with the emperor, he was appointed Royal Commissioner with total powers to end the opium trade in Canton. He arrived in Canton in March, 1839. Although Lin'due south vigorous effort to suppress the opium trade ultimately ended in disastrous war and personal disgrace, he is remembered a neat and incorruptible patriot eminently deserving of the nickname he had enjoyed earlier his appointment as an Purple Commissioner in County: "Lin the Blue Sky." Portraits of him by Chinese artists at the fourth dimension vary in way, only all convey the impression of a homo of wisdom and integrity. Today, statues in and even outside People's republic of china pay homage to the redoubtable commissioner. |

| Right: Commissioner Lin in scholar's robe Yale University, Sterling Memorial Library Correct: Lin Zexu Wikimedia Commons |  Wikimedia Commons Left: Lin Zexu, published 1843 Beinecke Library, Yale University |

| | |

| Statues of Commissioner Lin can exist found today in many places around the world, including Canton, Fuzhou, Hong Kong, Macao, and, pictured here, Chatham Square in New York City's Chinatown. Wikimedia Eatables |  |

| | |

| |

Source: https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/opium_wars_01/ow1_essay01.html

0 Response to "what product did western merchants choose to get the chinese to buy in large quanities"

Post a Comment